Shared space? More like wild space.

Imagine a street with no visible rules – no curbs, no markings, no traffic lights, no pedestrian crossings, and, most importantly, no signs dictating who has the right of way. Have you ever thought about what it would be like to navigate such a street? A space where pedestrians, cyclists, and drivers must instinctively collaborate, relying solely on eye contact and common sense?

This is the idea behind shared space, an urban design concept that works well in many Western European cities. But in Bucharest, it could quickly turn into urban chaos, where everyone makes their own rules.

Theory vs. reality – or why Bucharest isn’t Amsterdam

The shared space concept, developed by Dutch engineer Hans Monderman, suggests that in the absence of rigid traffic infrastructure, people become more attentive, cautious, and respectful. In theory, this approach makes streets safer and more inclusive—drivers slow down, pay attention, and yield to pedestrians. Cities like Amsterdam and London have successfully turned such streets into vibrant urban spaces where traffic self-regulates through mutual awareness.

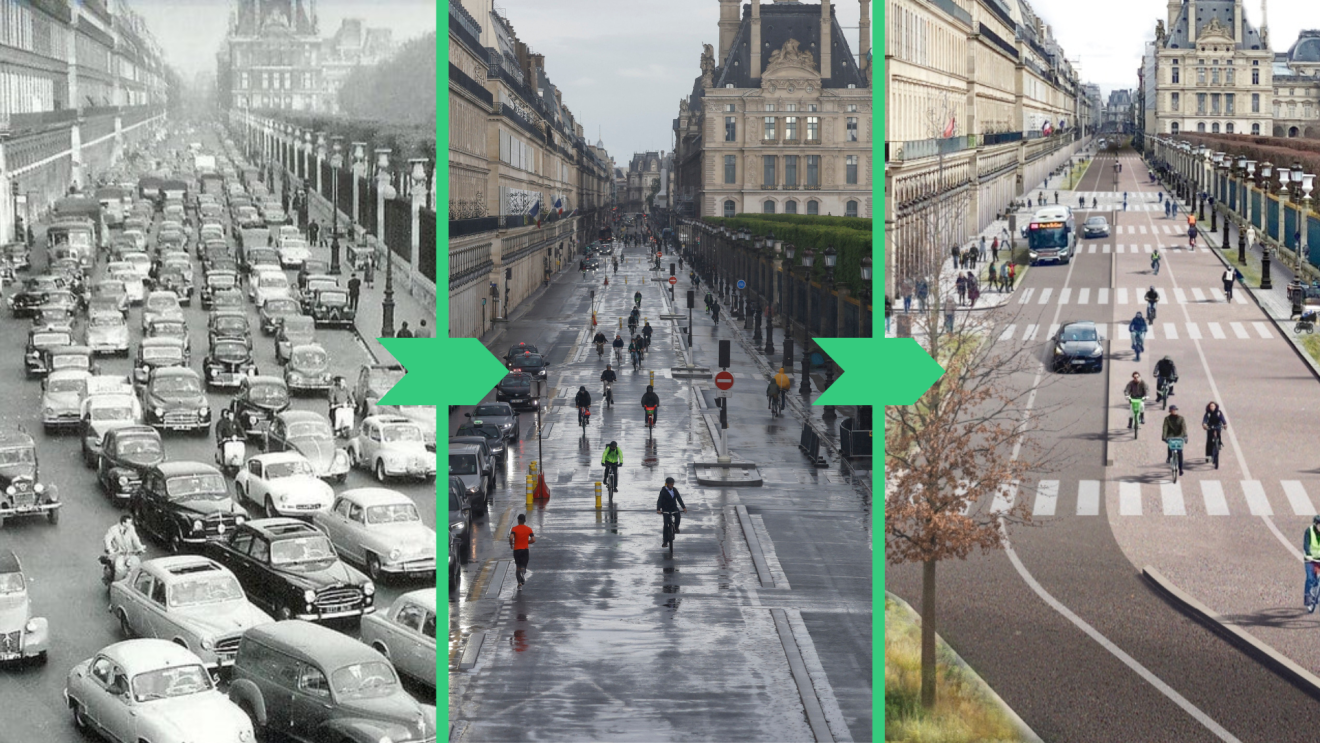

Paris took a bold step in this direction with Rue de Rivoli. Once a car-clogged boulevard dominated by honking and gridlock, the city gradually restricted vehicle access, reclaiming the space for people. Today, while not a pure shared space, Rue de Rivoli exemplifies modern urban mobility: cyclists and pedestrians enjoy ample room, public transport has priority, and air quality has significantly improved. What began as an experiment is now set to become permanent, reinforcing Paris’ vision of a more people-friendly city.

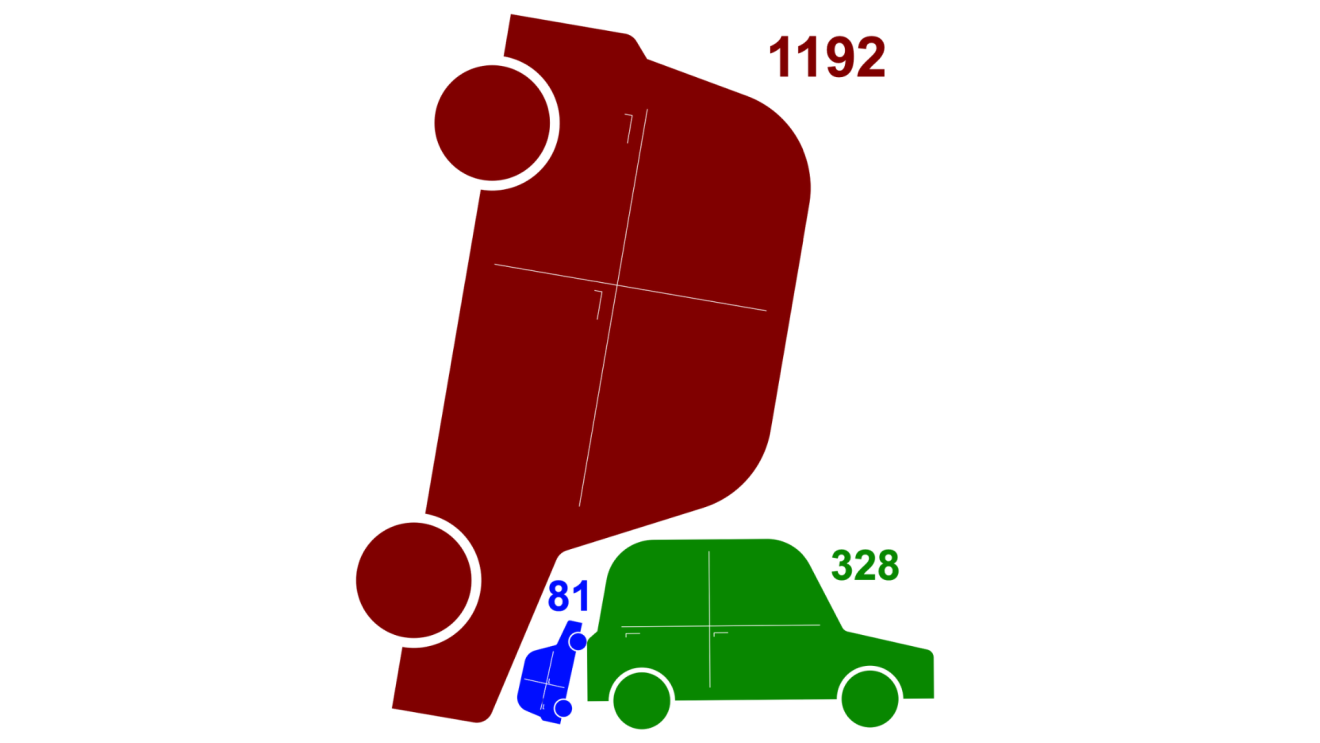

In reality, Romania is far from embracing the shared space model. Despite having the lowest car density in the EU (417 cars per 1,000 inhabitants, according to Eurostat, 2024), major cities—especially Bucharest—are overly congested. But the problem isn’t just the number of cars; it’s also how inefficiently they are used. For example, in Bucharest, the average vehicle occupancy rate is only 1.36–1.37 people per car (PMUD Bucharest-Ilfov, Technical Report 1), meaning most cars on the road carry just one person. Essentially, a huge amount of street space is occupied by very few people.

How did we get here? A mix of physical and psychological factors explains why Romania has turned into a traffic “paradise.” After 1990, the liberalization of the car market and massive imports of second-hand vehicles made cars widely accessible. Rising incomes, the removal of auto taxes, and the lack of efficient public transport infrastructure further fueled car dependency. In a society where cars represent not just a means of transportation but also a status symbol and a sign of independence, the idea of giving them up—even partially—triggers anxiety and resistance.

But the real issue goes deeper. Romania has a traffic culture defined by a lack of rule enforcement, chaotic parking, and an absolute prioritization of cars over all other modes of transport. So, the real question is: on a boulevard where even crossing at a traffic light is a challenge, what chance does a pedestrian have in a shared space?

What would it look like in Bucharest? Spoiler: a failed social experiment

If we were to implement a shared space on a central street in Bucharest tomorrow, the initial effect would be a kind of “beneficial confusion.” Drivers would feel uncertain, slow down, and become more cautious. But how long would that last? A week? Two?

Soon enough, the first “bold” driver would decide they can cut in front of pedestrians without consequence. Then another. Then a car would park illegally, followed by another, then sidewalks would get blocked. Before long, what was meant to be a shared space would devolve into a wild space—where everyone does as they please, and pedestrians are forced to find alternative routes.

We already have the legislation to make cities more people-friendly, but we lack enforcement rules.

What makes the situation even more absurd is that Romanian law already allows local administrations to redesign streets for a fairer distribution of space. The Urban Mobility Law (155/2023) clearly states that authorities can reduce traffic lane widths to 2.75 meters to create more space for pedestrians, bicycles, or public transport. Additionally, local councils have the power to reorganize streets and take steps toward a city designed with its users in mind.

In other words, the solution exists, but it’s not being used. Instead of making room for people, we dedicate every centimeter to cars. Instead of testing alternatives, we cling to the same models that have turned Bucharest into a daily traffic nightmare.

That doesn’t mean the idea of shared space should be entirely abandoned. It can work—but only as a transitional phase toward permanent pedestrianization. Cities like Paris and Barcelona have successfully transformed entire streets into pedestrian areas, but not overnight. First, car access was gradually restricted, and only later were the streets redesigned to prioritize walking and public transport.

A more realistic scenario for Bucharest, possibly even for segments of Calea Victoriei, would be the following:

Phase 1: Implementation of a shared space, with the removal of traffic signs and the widening of pedestrian areas.

Phase 2: Observing and adapting traffic – measuring how pedestrians, cyclists, and drivers react.

Phase 3: Permanent pedestrianization, once the residents have gotten used to the new model.

Bucharest is not ready, but it can learn.

Today, a shared space suddenly implemented in Bucharest would almost certainly lead to chaos. But that doesn’t mean we can’t build a more balanced city. Solutions exist: reducing car space, enforcing existing legislation, and using shared space as a transition method towards streets that are more people-friendly.

If we want a modern Bucharest, we must move from favoring cars to favoring residents. Let’s learn from examples that work in Europe and have the courage to apply solutions that truly transform the city. But for that, we need to move from words to actions, changing the urban behaviors we are used to. This is exactly what we’ll discuss at new Urban Habits, the festival organized by UrbanizeHub on April 26-27, which brings together experts, city creators, and communities to imagine and implement change. Otherwise, we’ll continue to get stuck in traffic, dreaming of more friendly cities, but without truly building them.

Image sources:

Exhibition Road, London (top) vs Pedestrian Zone in University Square, Bucharest (bottom)

Gradual transformation of Rue de Rivoli, Paris – 1, 2, 3

Comparative diagram of parked cars on a street in Bucharest – București. Minor Structure. Vision and methodology for organizing street space in the central area of Bucharest, developed by the World Bank.