Owning a car used to be a status symbol or an expression of personal identity, but younger generations today are much less interested in cars. They see mobility as a service, and themselves as its users. And as cars are becoming less popular, so is the act of driving. There are more and more attempts at introducing autonomous vehicles (AVs) on the roads – Uber is bringing its first self-driving cars to Pittsburgh, Volvo will start testing AVs with minimal driver intervention in New Zealand in November, and Amsterdam is testing driverless minibuses. But what does this mean for administrators of cities, and how will they respond to the growing pressures from companies and even citizens?

The introduction of AVs could have a major impact on cities in developing countries, jumping over decades of unsustainable transport policies. These regions often have a lower percentage of car ownership, so shared AVs could be the basis of a transport system, which could improve mobility, social cohesion, pollution, land use and urbanisation.

Cities need to consider the potential reduction in private cars and the resulting loss of public finances through the collection of less sales tax and fewer parking fees or fines. Private cars use up a lot of land in cities, but introducing AVs would create a major shift in parking trends.

Special routes?

Municipalities need to think about how AVs will be integrated onto roads, and how they’ll interact with regular cars. Although some variation will certainly exist between cities, from allowing AVs to use the same routes as regular cars to creating designated lanes, ‘some consistency in regulations on AVs will be necessary’, says Kathryn Urquhart from Low Emission Vehicles, C40 cities. For example, Oslo plans to ban private cars from the city centre – it could eventually introduce AVs to replace some of the vehicles that still remain in the area, like those dedicated to public transport. Other cities might want to do the same, but methods will certainly vary.

Fearing bugs and hackers

Technical errors or bugs could cause various issues, from minor incidents to fatalities. Software developers will be able to fix most of the problems relatively quickly, but there are still concerns about outside interference by criminals or terrorists.

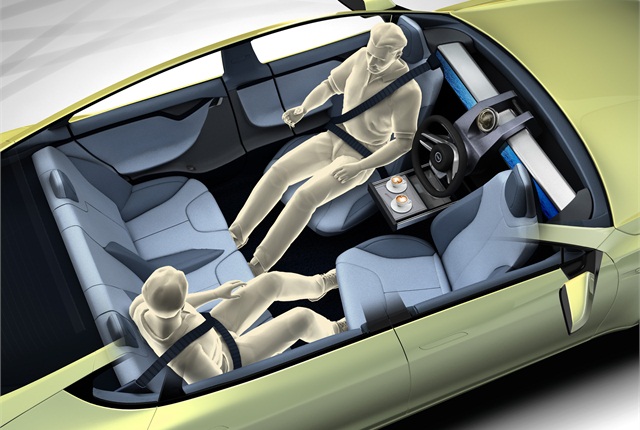

Experts say that although it seems that there would be more opportunities for hackers to infiltrate the systems, there is also a great amount of security on AVs and they are programmed to go into some kind of ‘safe mode’ or stop if they detect any kind of threat. The problem is that if the responsibility is taken away from the person in the car, they most likely can’t react quickly enough if the autopilot needs them to take full control, and those idle seconds are the most dangerous. A State Farm survey found that people expect to be able to do all kinds of things while the autopilot is on, like eating, reading or watching movies.

Inner-city or inter-city?

There’s a debate over whether AVs are a realistic solution for better urban mobility or whether they would be more useful for travelling between cities. Dave Marples, Chief Scientist at Technolution BV, thinks that drivers will probably use manual mode to navigate cities, where driving is more complex, and switch to autonomous on motorways.

Autonomous vehicles will certainly be disruptive for the normal rhythm of city traffic, and authorities need to prepare for the challenges consistently by having long-term plans, whether they involve a redesign of the whole transit system or implement some changes in parallel with the old infrastructure.

Sources: cities-today.com, claimsjournal.com, ecowatch.com, citylab.com, nzherald.com

Photos: automotive-fleet.com